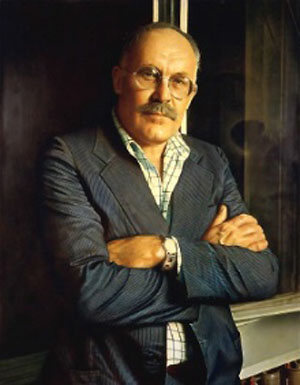

Philip Brophy

Vox

Gertrude Contemporary Art Spaces, 200 Gertrude Street Fitzroy, Melbourne Sep-Oct 2007

In a recent conversation with Melbourne artist Lou Hubbard, she pointed out that the nexus of Brophy’s work is his fascination with communication. Communication, or more to the point engendered or sexualised communication – how we do it, why we do it and the slippages that occur between what’s on the surface and what’s really being said.

Using logo and branding, Brophy pushed VOX like a consumable product. Treating the GCAS shop-front like advertising space, he generated considerable excitement about his new work. Vox interacted successfully with the window in a way that I hadn’t seen since Spiros Panigirakis’ – albeit very different project – Without, in January 2006.

After recovering from the disappointment of not actually seeing the video component of Philip Brophy’s work at the opening (don’t be under the popular misconception that people don’t view artworks at openings) I went back during the last week of the exhibition for another look.

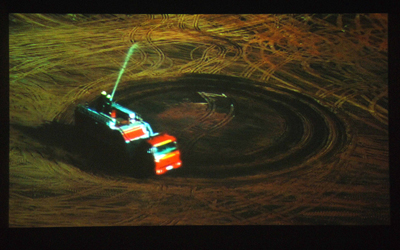

I can forgive VOX its technical flaws because it’s more the content of Brophy’s work and his particular vision of the world that I find so interesting. The GCAS media release presents VOX as a ‘sexualised visualisation’ of the romantic comedy, but it’s not simply a subversion or interpretation of a chick/dick flick, it’s also a sad anthropological study of what we humans do and say to one another on a daily basis; love me, fuck me, want me, understand me. This combination of insights into gender, sexuality and semiotics combined with his glam rock, Ziggy Stardust aesthetic is what draws me in. But a level of presentation that’s as sophisticated as the work is insightful will keep me coming back.

Meredith Turnbull

Gertrude Contemporary Art Spaces, 200 Gertrude Street Fitzroy, Melbourne Sep-Oct 2007

In a recent conversation with Melbourne artist Lou Hubbard, she pointed out that the nexus of Brophy’s work is his fascination with communication. Communication, or more to the point engendered or sexualised communication – how we do it, why we do it and the slippages that occur between what’s on the surface and what’s really being said.

Using logo and branding, Brophy pushed VOX like a consumable product. Treating the GCAS shop-front like advertising space, he generated considerable excitement about his new work. Vox interacted successfully with the window in a way that I hadn’t seen since Spiros Panigirakis’ – albeit very different project – Without, in January 2006.

After recovering from the disappointment of not actually seeing the video component of Philip Brophy’s work at the opening (don’t be under the popular misconception that people don’t view artworks at openings) I went back during the last week of the exhibition for another look.

I can forgive VOX its technical flaws because it’s more the content of Brophy’s work and his particular vision of the world that I find so interesting. The GCAS media release presents VOX as a ‘sexualised visualisation’ of the romantic comedy, but it’s not simply a subversion or interpretation of a chick/dick flick, it’s also a sad anthropological study of what we humans do and say to one another on a daily basis; love me, fuck me, want me, understand me. This combination of insights into gender, sexuality and semiotics combined with his glam rock, Ziggy Stardust aesthetic is what draws me in. But a level of presentation that’s as sophisticated as the work is insightful will keep me coming back.

Meredith Turnbull