Colette

Colette says everything with the utmost elegance and precision. In Cheri and The Last of Cheri, written towards the end of her career, Colette is consistently drop-dead funny in a social comedy kind of way, but her comedy is shaped into the most heart-rending, psychological depiction of the inevitabilities of estrangement, sadness, distance, age. Colette is Proust within a champagne bubble. The courtesans decorate their boudoirs in pink silk, read the financial trades, deal behind each other's backs in rubber futures. Colette, like the filmmaker Almodovar, loves and recognizes women as only a drag queen can.

Approaching 50, Lea, Cheri's heroine, is like a grown-up Claudine. Like Claudine in her adolescent omnipotence, Lea knows everything but, unable to keep her 25 year old lover from pursuing his own future, what good does knowledge do? With caustic grace, Lea becomes an earthy wise-cracking old woman, a parody of Colette's 19th century predecessor, George Sand. But each of Colette's scenes is perfect in its incandescence, and even more miraculous when read as parts of the whole: exquisitely positioned pieces of a larger narrative, cumulative and whole.

Here in Albuquerque, New Mexico, Colette is the muse de jour of all the local dykes. I sit on the bed in my one bedroom secretary condo reading her, when it's too hot to go outdoors.

Chris Kraus

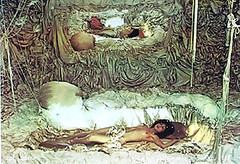

see Lowe's comment about this image, Colette 'Real Dream (Sleeping Performance)' 1975